Unlawful Governance

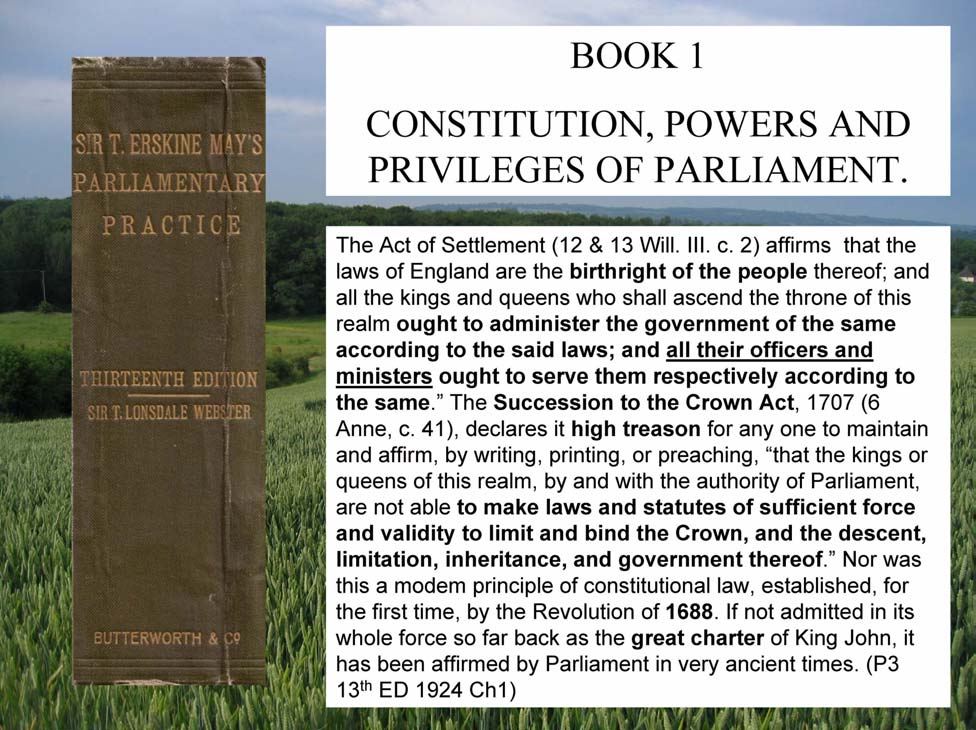

The text highlighted here shows unequivocally that our Constitutional law is paramount

The above is an extract from Parliament’s very own hand book Erskine May. The high treason penalty was repealed in 1967, nevertheless the principle remains and is utterly clear.

THE Principles of our Constitution are fundamentally self-preserving and allow no provision for its dismantling, diminishment or destruction. The rules of law and custom that determine that we have as a ‘birthright’ our liberty are all the prerequisite duty of office to uphold and maintain. All this is sworn to be upheld by those who take up any office, under the Crown. We all have the responsibility of preserving and protecting this gift from our forbears so that in turn, every future generation may benefit from and enjoy this liberty under the rule of their laws. The gift of the power of self-determination is the true birthright of liberty.

The birthright of Englishmen depends upon the supremacy of the rule of law, its observance and their right to control their laws, their content and making. The right of selfdetermination under the rule of our own law is the very fabric of England’s liberty. Our liberty is protected in the particulars of our constitutional law and Parliament’s overriding duty is to maintain and preserve those freedoms. Parliament’s power is not arbitrary or absolute. When it is said that ‘Parliament is Sovereign’ it confirms the supremacy of the law and the supremacy of our constitution and Parliament’s duty and responsibility to uphold and maintain both. What is meant but often misunderstood or ignored, is that the highest power known to the Constitution is the rule of law. This is the greatest power in comparison with the other subordinate powers established by the law under our Constitution. “Be ye King or Commoner the law is above you”- Sir Edward Coke.

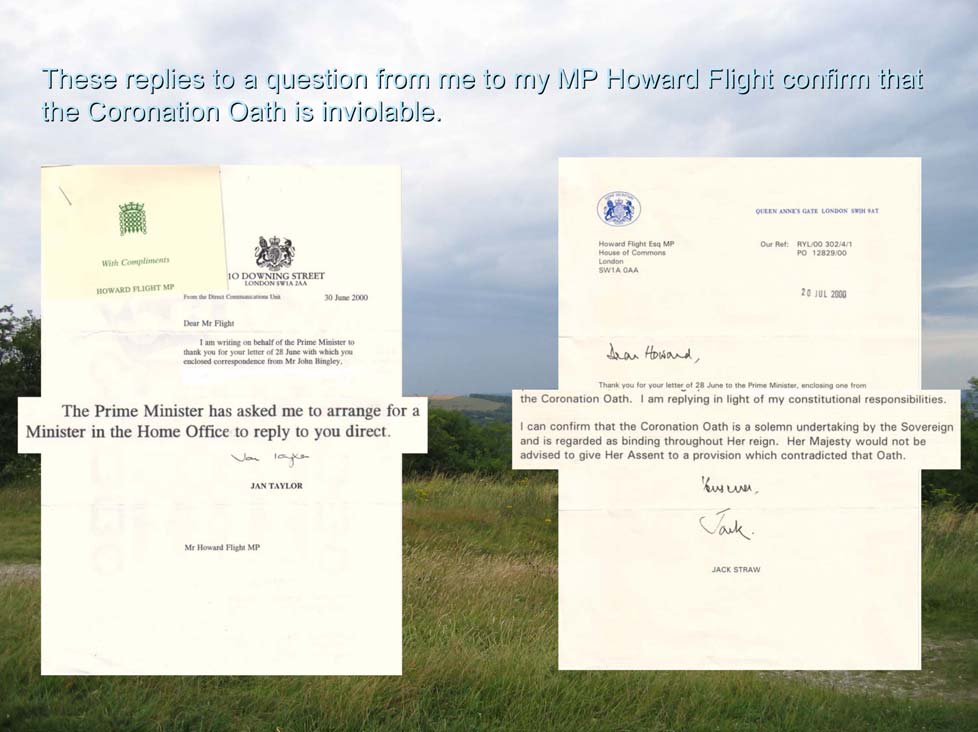

If the powers of governance pass to those whom the electorate cannot dismiss, or if juries are not wholly responsible for determination of verdicts, then we are in a state of arbitrary power that is diametrically opposed to the rule of law and liberty. The rule of law is an integral process of the Constitution and ensures: – The constitutional separation of power, independence of the Judiciary, of parliamentary debate, of the prerogative of the Monarch’s Royal Assent contracted to the Constitution, the presumption of innocence, trial by jury (true people power lies here, by controlling the power of the state to convict) coupled with the right of Habeas Corpus and much more. The guarantee of adherence to all this is assured through oaths of office. The Coronation Oath is the penultimate entrenchment. It secures the Constitution during the Monarch’s reign to be only by the rule of law, both statute and common and the custom.

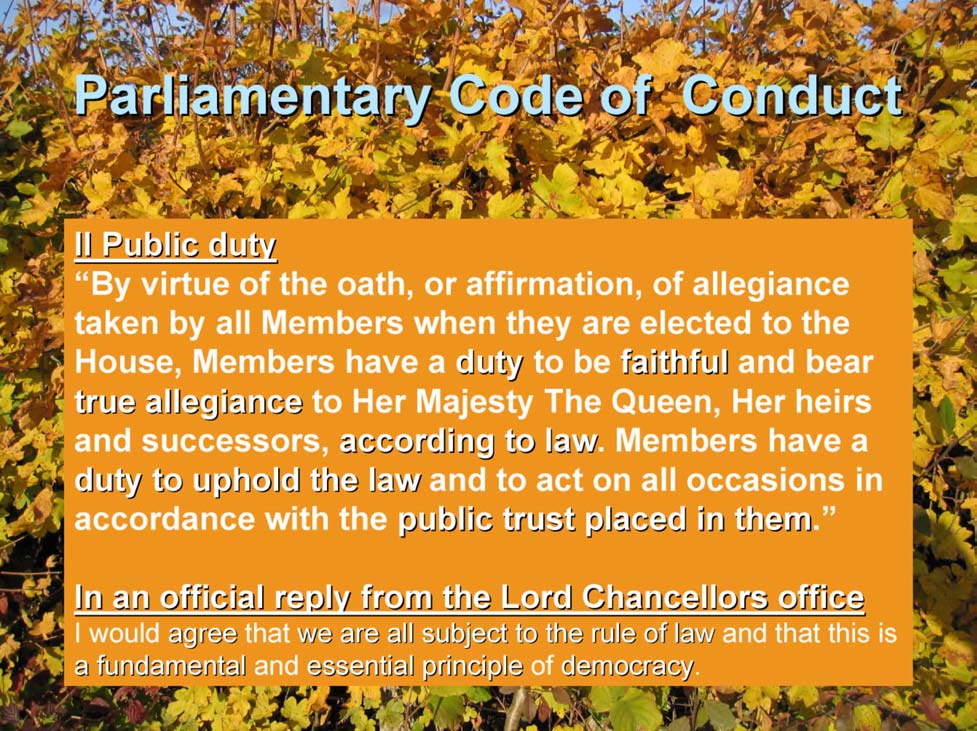

The parliamentary reply above confirms that no minister may advise a breach of the coronation oath.

This entrenchment may be proved by examining some fundamental concepts of our Constitution which may be used to reveal the true limitations of Parliamentary power beyond which governance becomes irregular, unconstitutional, and without legitimate authority.

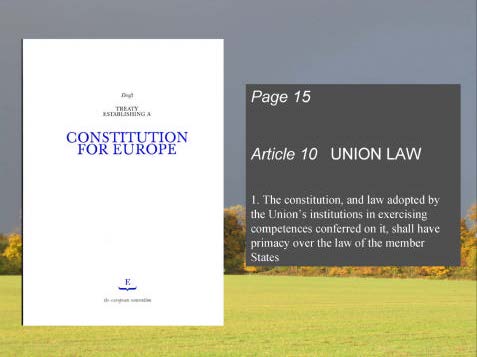

The proposed EU Constitution is in this category and our present Government is the latest of many governments to breach the English Constitution. This Parliament with the acceptance of the Nice Treaty has continued to pass power of governance abroad; its clear intention is to maintain this constitutional defiance. No Parliament has any legitimate authority to pass the governance of this nation to a third party who may be wholly or partially unaccountable to, unelected by, or irremovable by the electorate of the UK. Under our existing Constitution there never can be any legitimate political power to pass powers of governance to those who owe no allegiance to the Crown or obligation and duty to the People of the United Kingdom. There may never be any legitimate secession of sovereignty to an alien power. Delegation must always be specific and subordinate; otherwise allegiance is breached and sovereignty broken.

This clause of the EU constitution is clearly unconstitutional. If it were accepted it is hard to see how a petition of right could fail to have it declared unconstitutional and thus void! By What Authority may any body defy the law of our constitution?

First we must consider the concept of ‘constitution’. At its most fundamental the purpose of any form of constitution or constitutional law is to impose some order and form to a state. In England we are said to have an ‘unwritten constitution’ yet at the same time to have a ‘constitutionally limited monarch’. This may seem a paradox but it is simply explained. The first point is that the English Constitution is composed of many parts and the whole edifice is not codified into a single constitutional document. It does not equate to our having no written constitution. Such famous scripts as Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, the Declaration and Bill of Rights are all constitutional. We can clearly see there are many written facets to our Constitution which are scattered through our history. Second, the Monarchy is said to be ‘constitutionally limited’. This is undoubtedly true and crucially the same constraints apply to Parliament, as will be shown. We are in the midst of a battle of usurped parliamentary power versus constitutional principle. As a result the rule of law, complete with our freedom of independence and liberty in short our whole birthright, is at stake. Our politicians are not elected or empowered to disenfranchise us from our birthright of self-determination. They represent the will of the people in Parliament for the purpose of governing only in accordance with our law and constitution. A defined, not an unlimited purpose.

If it is accepted that the basic principle of any constitution is to give structure to the state, it follows that there must be some means of achieving this constitutional definition by a logical system of law or code. Therefore if the people are to be assured of liberty and freedom under thier constitution, a fundamental purpose must be to restrain the executive and legislative body from absolute power. Further there must be a system of redress that allows any citizen to check the constitutionality of power asserted and prevent or rectify any unlawful assertions or abuse. All these principles feature in the English Constitution.

Current political and judicial thinking is to suppose that parliamentary sovereignty is unlimited and may literally extend to anything it chooses. Professor A.V. Dicey promulgated the authoritative views of Sir William Blackstone, the first Vinerian professor of law at Oxford University, but failed to take full cognisance of the fundamental purpose and limitation of Parliament about which even Blackstone is inconsistent. This inconsistency of absolutist power was compounded by lectures and writings on constitutional law by Professor A. V. Dicey between 1885 and 1926. Dicey believed the only constraint was public opinion expressed at elections or the supremacy of the law. In 1931 a government committee on administrative power reported in this vein: – The Committee on Minister’s Powers Report (Cmd paper 4060 @ page 20). To emphasise the power available to Parliament they said ‘Parliament is supreme and its power to legislate is therefore unlimited.’ They went on to cite an Act for the boiling to death of the Bishop of Rochester’s cook by Henry VIII (22Yr H. VIII Ch9. An Act Against Poisoning) as an extreme example of legislative power.

The picture below focuses upon the actual words from the statute (held by the House of Lords Records Office) of the act against poisoning of 1531.

Richard Roose shalbe therefore boylled to death

There is reference in (vol 4 page 83) ‘The Parliamentary History of England’ published in 1751 by Thomas Osbourne & William Sandby

“Hall mentions another act, in that whoso poisoned Any person, should be put into hot water and boyled to death. This Act was made, adds he, because one Richard Roose, in the Parliament Time, had poisoned divers Persons in the Bishop of Rochester’s Palace, for which fact he was boiled in Smithfield.”

This unlimited view of Parliament’s power whilst de facto in Henry VIII’s time was always unconstitutional. This is a fact that Blackstone notes and says was exemplified by Henry VIII’s Act of Proclamations of 1539;

“It must however be remarked, that (particular (sic) in his later years) the Royal prerogative was then strained to a very tyrannical and oppressive height; and, what was the worst circumstance, its encroachments were established by law, under the sanction of those pusillanimous parliaments, one of which to its eternal disgrace passed a statute, whereby it was enacted that the King’s proclamations should have the force of Acts of Parliament; and others concurred in that wild and new fangled treasons, …” (4 Vol Bl Comm P424)

In 1628 there was the Petition of Right which amounted to an assertion of the liberty of the subject over the unfettered use of prerogative which itself was used to suspend and dispense with the law. The concept of the Divine Right of Kings and the abuse of power that it represented was curtailed. The Star Chamber, the most arbitrary of courts, was abolished and the prerogative regulated by statute. The Ship Money, a contentious tax, was abolished on grounds of ‘no taxation without representation’. All this was done in Parliament. Charles I begrudgingly accepted the terms but was soon in dispute and finally was executed in January1649.

Following the Revolution of 1688, limitation was placed upon the Monarch and Government by changes to the Coronation Oath and by the Declaration and Bill of Rights 1688/9. This was an undoubted limitation upon the source of all governing power. Sir William Blackstone dedicated a short chapter of his commentaries to the ‘Duties of the King’ which he regarded as certain. One such duty or limitation was that the Declaration and Bill of Rights were to be followed and observed as the mode of government.

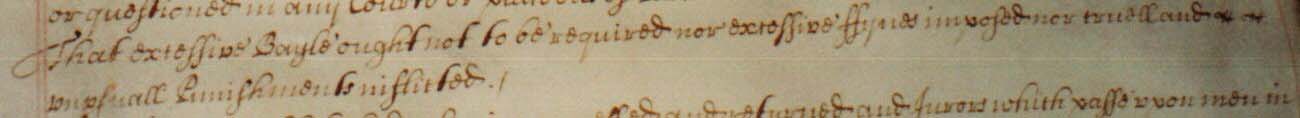

The Declaration of Rights 1688 amongst other things outlawed all cruel and unusual punishments. Today it is once again being asserted that Parliament has the same unlimited powers as had Henry VIII. Our Constitution clearly sets out that it does not. Below is the clause in the Declaration of Rights which prohibits torture and barbarous inquisition. The words depicted read as follows:-

“That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed; nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

Note the words “nor cruel and unusual punishments”. This vital clause is but one part of a constitutional bulwark against the tools of oppression which reside in our Constitution.

It is an unfortunate fact that many people including numerous politicians and even lawyer do not realise that we have a huge amount of extant written constitutional law with little conception of its true meaning! It sole purpose is to regulate or limit all powers of governance and it quite definitely applies to Parliament. Parliament is certainly not free to reintroduce boiling even for convicted terrorists. The monarch is constitutionally restrained by our laws which are constitutional in content. The power to enact a bill and thus make law is that of a constitutionally limited Royal Assent.

Our present government is heading deeper into unconstitutional territory at an ever increasing pace. If constitutional remedy is sought where there is a proven breach, remedy may not be lawfully denied by any court. If redress is not given it can readily be seen that arbitrary power has taken hold and denied the means of redress. Our Constitution affords several means to ensure our remedies. The fundamental principles are contained in Magna Carta and its descendants. Redress must be sought by all legitimate means but ultimately there is a constitutional right of resistance until such time as redress is made. The nature of such resistance is defined in the Magna Carta. These were not just empty words or without force but enshrined principles for legitimate governance through the law. This power of the Constitution was fully appreciated by Sir Winston Churchill and illustrated by this quote:-

“The facts embodied in it and the circumstances giving rise to them were buried or misunderstood. The underlying idea of the sovereignty of the law, long existent in feudal custom, was raised by it into a doctrine for the national State. And when in subsequent ages the State, swollen with its own authority, has attempted to ride roughshod over the rights or liberties of the subject it is to this doctrine that appeal has again and again been made, and never as yet, without success.”

Churchill, A History of the English Speaking Peoples (1956).

Despotism and tyranny rely upon absolute power and its enforcement. The EU is proving to be a ratchet system of treaty making, designed to accumulate ever more power in fewer and less accountable hands. This ratchet is being progressively tightened and the principle of selfdetermination is now under direct assault. Tyrants will seek to control and deny redress to those who oppose them whilst extending their own sphere of influence and comfort. They will subjugate and oppress. The EU by its latest measures is making provision to fund supportive political parties whilst at the same time making rules that ensure that political parties which are against the federalist agenda will not be eligible for funding and may even be prohibited. The ancient writ of Habeas Corpus is being sidelined by treaty and with it the control of conviction for those who are extradited without trial. How can such persons be said to be under the protection of our law? They will not benefit from the presumption of innocence, nor Habeas Corpus nor from their just right of trial by their peers. This is all plainly unconstitutional.

It is said that in England ‘a man is born free save under due restraint of the law’. HIS LIBERTY IS THE LAW. It is government’s primary constitutional duty to maintain that freedom. The English Constitution affords an Englishman’s liberty, complete protection under the law assured through the oaths of office combined with the separation and balance of power. It is his peers who may convict him at trial, not the government by decree. Our constitutional laws prohibit assertion or accumulation of absolute power. Power of enactment is only by the concurrence of our tripartite system, consisting of the Lords and Commons and exercised by the Monarch’s grant of Royal Assent. The assent is the grant of the power which itself is a prerogative of constitutionally limited authority. It is the grant of Royal Assent that promotes a bill to the power of the statute law. Illegal use of prerogative cannot be said to make good or legitimate law; the proof lies in the constitutional events of the seventeenth century that caused and effected the limitation of our monarchy and governance by contract.

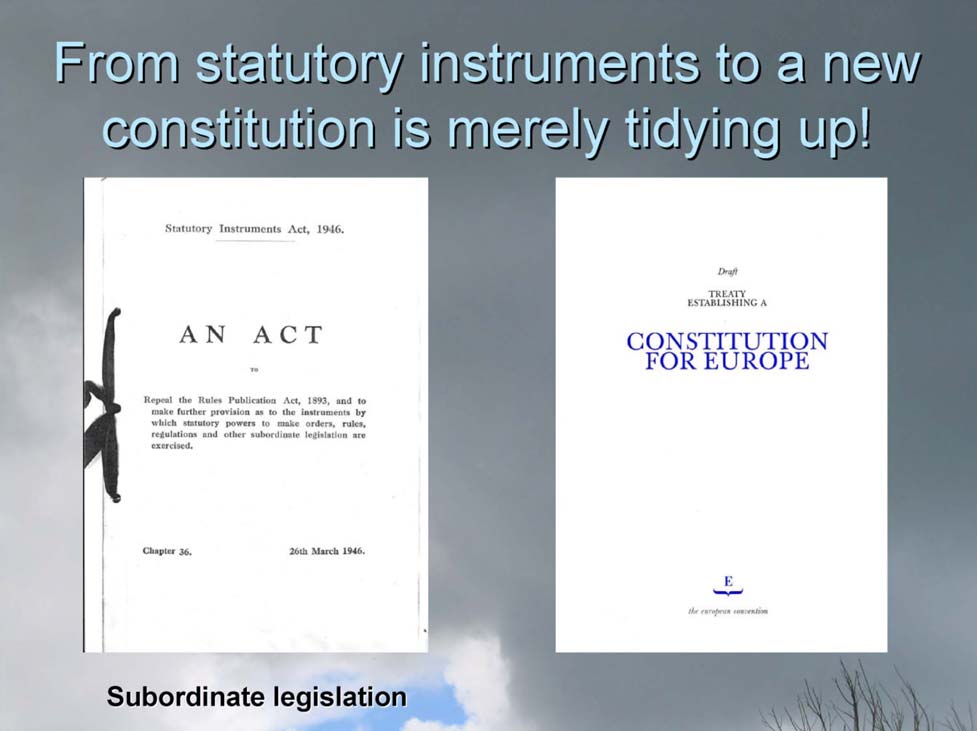

In 1929 the Rt Hon Lord Hewart of Bury, Lord Chief Justice, wrote a book The New Despotism. Its criticism was centred on the bureaucratic tendency to provide ministers and officials with excessive powers. General clauses had begun to appear in bills giving powers to the minister to ‘make such regulation as is necessary to resolve any difficulty under this act’ and ‘that the minister’s words will be final and as if part of this act’. Lord Hewart pointed out that this was a tendency to separate the people from their courts by giving law-making powers to ministers who would become licensed despots. It was this book which instigated the ‘Committee on Ministers’ Power’ of April 1932 which in turn led to the Statutory Instrument Act of 1946. Lord Hewart made clear the insidious danger in allowing such powers to exist because he predicted they could undermine the whole function and responsibility of Parliament. The due process of the rule of law could thus be undermined by the law itself (particularly by subordinate regulations). Ministers were making regulations arbitrarily to further their pet policies and usually heading any tribunal to which appeal could be made, with the minister concerned apparently having the power arbitrarily to determine the outcome. Policy was becoming the governing factor without account to the rule of law, in short, a degree of despotism. Hewart espoused the Dicean view without defining the fault line, namely that the rule of law is an inseparable constitutional process hingeing on people power through the jury for its enforcement; not raw power emanating from the top, down. It was Hewart who famously said that justice must be seen to be done. The ‘Rule of Law’ is entrenched in our Constitution and therefore cannot be ignored or abandoned. To obey the law is the fundamental, constitutional, prerequisite to duty, of holding any office under the Crown and indeed the duty of all who owe allegiance. Without this the Constitution fails and despotic authority gains power.

The Act pictured above shows the true status of all regulation as subordinate legislation. Administrative government has largely come into being since 1946, the fundamentals of our Constitution were settled over 300 years ago. Administrative law is undoubtedly subordinate to the Constitution.

It is a matter of constitutional fact that the Prime Minister whilst appearing to wield great power possesses none which may breach the Constitution. His powers are actually those of the Monarch’s Prerogative and those which the law allows him. All use of the prerogative is under the limitation imposed by our Constitution. That limitation may not be lawfully set aside. By convention the Monarch accepts the advice of ministers all of whom are sworn to be constrained by the laws of our Constitution. Blackstone pointed to the right of refusal of Royal Assent as being the ‘negative power’ vested in the Crown and one of the prime checks upon misapplication of power. It is a maxim of the constitution that “the Monarch can do no wrong but only prevent wrong from being done”. The Monarch will accept the advice of ministers but nevertheless is under clear constitutional restraint not to accept that which is plainly unconstitutional which of course should not be proffered in the first place. There are many laws which support the Constitution:- treason, misfeasance in public office, contempt of statute and perjury to name but a few.

Sir Robert Megarry V-C Manuel v Attorney General 1983 (C.A.)

“As a matter of law the courts of England recognise Parliament as being omnipotent in all save the power to destroy its own omnipotence.” The omnipotence mentioned in this quote equals the whole Constitution. There is no enabling constitutional authority bestowed on Parliament to destroy or diminish the very Constitution which is the source and foundation of its authority. The very opposite is actually the case.

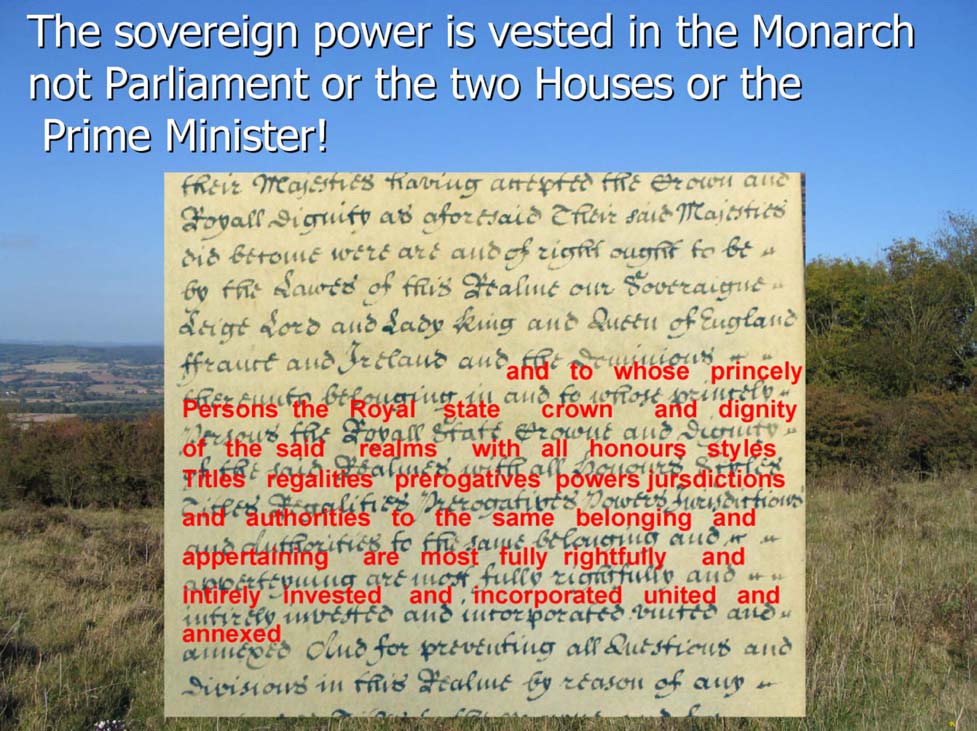

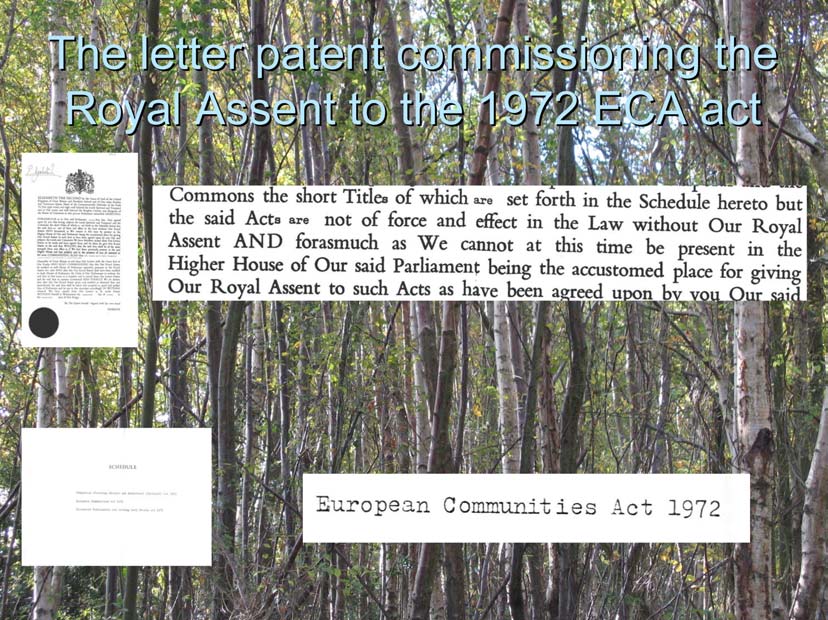

The extract above from the Bill of Rights prove that constitutionally, Sovereign power is vested with the Monarch. Whilst the context and content of Bills are determined in the two Houses of Parliament who then submit the Bills for Royal Assent. Below a letter patent which authorised Lord Hailsham to give Royal Assent to the acts specified on the separate schedule which included the European Communities Act 1972. See the highlighted text in both pictures. ( NB:- not of force or effect in law without our Royal Assent)

Historically power has always led to a conflict between law and liberty. When power to govern and power to enforce, combine and fall into solitary hands, tyranny and despotism may flourish. Sir William Blackstone made much of the separation of powers and made plain that our liberty depended upon the equal and tripartite distribution of checks and balances. He warned that if it should ever happen that it became unbalanced, despotism could and would soon follow.

Because such events have occurred in our history we have examples from which lessons were learnt and remedies brought into our law. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 is probably the most formidable and Magna Carta the most fundamental. They confirmed the existence and strength of our Constitution. They created suitable legal restraint with separation of power, complete with the necessary remedy to steer us back to the constitutional path. The whole system is dependent upon the Rule of our Law and having an independent judiciary whose authority is to uphold only the law under the Constitution. Professor Dicey alluded to this in his summary of the supremacy of the law. At page 472 of his 9th edition of An Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution : –

The “rule of law” is a conception which in the United States indeed has received a development beyond that which it has reached in England; but it is an idea not so much unknown to as deliberately rejected by the constitution-makers of France, and of other continental countries which have followed French guidance. For the supremacy of the law of the land means in the last resort the right of the judges to control the executive government, whilst the separation des pouvoirs means, as construed by Frenchmen, the right of the government to control the judges The authority of the Courts of Law as understood in England can therefore hardly coexist with the system of droit administratif as it prevails in France. We may perhaps even go so far as to say that English legalism is hardly consistent with the existence of an official body which bears any true resemblance to what foreigners call ‘the administration’. To say this is not to assert that foreign forms of government are necessarily inferior to the English Constitution or unsuited for a civilised and free people. All that necessarily results from an analysis of our institutions, and a comparison of them with the institutions of foreign countries, is, that the English Constitution is still marked, far more deeply than is generally supposed, by peculiar features, and that these peculiar characteristics may be summed up in the combination of Parliamentary Sovereignty with the Rule of Law.

Dicey was generally correct in his thesis but he omitted to consider the fundamental constitutional limitations inherent within the laws in force. He did not consider the Constitution had placed limitations upon law-making powers of governance, in either statute or other form. However he acknowledged the supremacy of the law. This is propounded from Blackstone. Blackstone fully acknowledged the settlement of the Glorious Revolution and that it set definite limits to the use of the prerogative defined by the Declaration and Bill of Rights etc. The limitation of the Monarch by lawful control of the prerogative is therefore unquestionably a limitation upon all the powers of governance. It cannot be otherwise. The absurdity of asserting otherwise can be simply demonstrated in the natural conflict which arises when the constitutional law is in contradiction to the designs of Parliament as exemplified by the conflict inherent in accepting the EU constitution in breach of the British oaths of allegiance to the Crown. Worse still are Parliament’s enactments which are in oppression of the subjects’ liberties. Blackstone is emphatic that the preservation of the liberties of the subject is the duty of all who govern. He called the rights and liberties absolute. He points out the duty of preservation of our liberties as being beyond doubt. The Coronation Oath is the contract by which the Monarchy is bound to exert only lawful power which is again promised to be the only power that may be lawfully asserted in the courts. He refers to the Coronation Oath as being a contract beyond any doubt:-

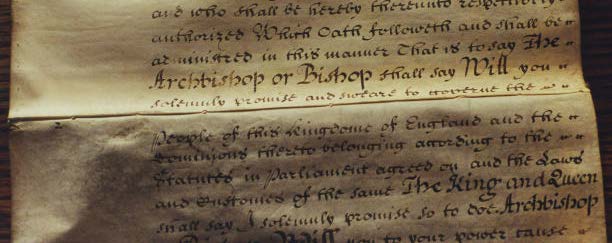

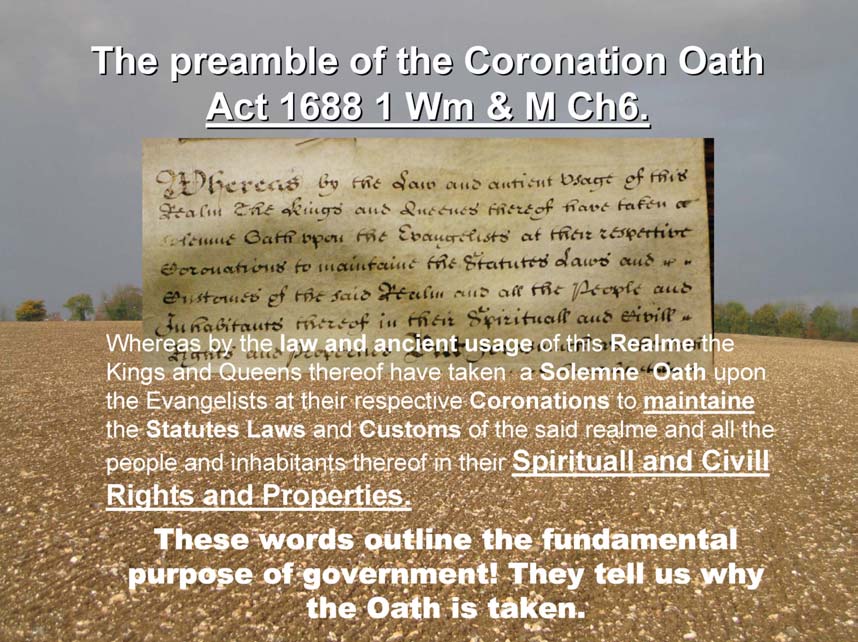

On the next page is an extract of the Coronation Oath Act of 1688/9 (1 Wm & M Ch6). The photo highlights the words which forced the Monarch into a constitutional limitation. The Words “govern according to the Statutes in Parliament agreed on” were not in the oath of

Sir William Blackstone 1723-1780

The Coronation Oath

“However, in what form it so ever be conceived, this is most indisputably a fundamental and original express contract”

“…… And to reduce that contract to a plain certainty. So that whatever doubts might be formerly raised by weak and scrupulous minds about the existence of such an original contract, they must now entirely cease; especially with regard to every prince who has reigned since the year 1688.”

James II or his predecessors. It was this addition to the Coronation Oath at the Glorious Revolution 1688/9 which defeated the Divine Right of Kings. These are the written words that altered the course of history and the English Constitution permanently. Never again could the King rule by absolute power. Thenceforth there was to be no doubt that the rule of law was supreme, not policy or politics but the law was confirmed integral and inherent in our Constitution. The Revolution was not a victory for parliamentary power but of the certainty of the ‘supremacy of the rule of law’. This last fact is not considered or even realised by those who blindly trumpet the mantra of the ‘Sovereignty of Parliament.’ They pay no heed to the Constitution as written and its constraints.

The Coronation Oath Act 1 Wm & M Ch 6 1689

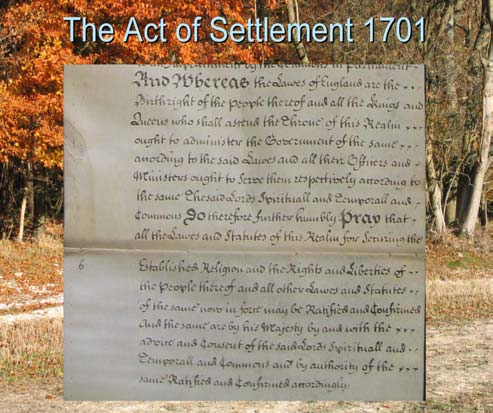

To show that the laws of constitutional content control all powers of governance Blackstone quotes the Act of Settlement 12 & 13 W III c2 (1702). There is no doubt that the Bill of Rights was a law to control and limit the powers of governance and therefore limit the use of prerogative of Royal Assent. Consider carefully the words below from the Act of Settlement and repeated elsewhere in our statutes:-

“And Whereas the laws of England are the xxx

Birthright of the people thereof, and all the kings and Queens who shall ascend the throne of this Realm xxx

ought to administer the government of the same xxx

according to the said laws, and all their officers and x

Ministers ought to serve them respectively according to the same, the said Lords Spiritual and Temporal and x

Commons Do therefore further humbly Pray that x

all the laws and statutes of this realm for securing the Established religion and the rights and liberties of xx

the people thereof, and all other Laws and Statutes xx

of the same now in force, may be ratified and confirmed and the same are by his Majesty by and with the xxx

advice and consent of the said Lords Spirituall and xx

Temporall and Commons, and by authority of the xxx

same, Ratified and Confirmed accordingly:

The picture and text of the Act of Settlement are of the actual parliamentary roll of 1701. The xxx were the method used to justify the text to the right margin and limit the ability for alteration.

This point is of the utmost importance and has never apparently been the subject of a court decision. Here is certain proof that our law of the Constitution limits Parliament. Additional proof for this is scattered about our case law but has never been fully tested. The laws that lay down the liberties of the subjects are laws which control all government; our constitutional law says so. The Supremacy lies in the rule of law not in Parliament. The ultimate embodiment of this comes with the concept of the Judiciary overturning an Act of Parliament because it is in conflict with the Constitution. The recent challenge in McWhirter and Gouriet v Foreign Secretary in March 2003 calling for a judicial review of the Nice Treaty was refused in essence because the judges claimed that there was no power in the court to overturn an act of Parliament. This is not what the law of our Constitution determines or requires. First the Declaration and Bill of Rights determine that the subject has a number of absolute rights. These were intended to be entrenched and placed beyond the means of ordinary legislation to repeal or diminish by limiting the Crown and therefore Parliament. They limit and control the use of all prerogative powers (eg Royal Assent). The clauses which direct as to how the articles of the Declaration and Bill must be observed are emphatic and directory. They allow no room for any thing to be taken in ‘consequence or example’ against them. They are then specifically made the duty ‘of all officers and ministers whatsoever’ and again it is directed that ‘they shall be esteemed, allowed, adjudged, deemed and taken to be’. This is the emphatic language of our current constitutional law and no new law has directly repealed or overridden it. It is the law by which all are contracted to govern. By what authority may ministers ignore this constitutional limitation? There can be and is no legitimate power available to them. There is no authority in our constitution which allows the monarch to be deceived in grant of the power of Royal Assent. The Coronation Oath determines that it is mandatory upon the administration for ‘law and justice in mercy to be used in all judgements’. Being that there are no newer laws to direct the fundamental scope of the prerogative, it is plain and quite beyond any doubt that both the Declaration and Bill of Rights are extant. Desuetude (A state of disuse OED) is unknown to the law of England. Indeed Madam Speaker said in the House of Commons on 21 July 1993 “the Bill of Rights will be required to be fully respected by all those appearing before the courts.”

The great precedents for asserting the Rights and liberties of the Subject are Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights of 1628 and its redress being forced upon the respective Monarchs. Next there was the more elaborate settlement of 1688/9 in the Declaration and Bill of Rights, the Coronation Oath and then the subsequent Acts of Settlement 1701. The Bill of Rights confirms with the force of a statute law the ‘ratifying confirming & establishing’ the articles of the prior Declaration. The certainty of a right to a remedy, against any constitutional infringement is encapsulated in these documents. It is of course a constitutional necessity that there is a means for the individual to assert the constitution however it may be breached. The Constitution confirmed the absolute right of the subjects to petition the Monarch (a way of seeking redress) and prohibited any means of making this illegal or regulating it. Here is an extract from the Declaration of Rights 1688:-

“That it is the right of the subjects to petition the king, and that all commitments or prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal. ……………. And they (the people) do claim demand and insist upon all and singular the premises as their undoubted rights and liberties and that no declarations judgements doings or proceedings to the prejudice of the people in any of the said premises ought to be taken into consequence or example).

The importance of this is that it demonstrates the mandatory nature that is deemed and must of necessity exist on behalf of the subjects to enforce their supreme rights over all mis governance. The appeal by the right of petition is aimed directly at the constitutional source of the power. This was therefore intended as the means to control abuse wherever it may occur. For everything other than the rule of law itself is subordinate in constitutional principle. The power is accountable to a fixed standard and redress is mandatory if there is a breach. Normally petition should not be necessary for the courts are fully empowered to ‘allow adjudge and take to be’ the rights and liberties of the subject which must be held and esteemed by all, above all else. This is the law of our constitution as it stands today, it is not optional, it is not discretionary it is mandatory upon ministers and the Crown. How can it be said that the passing of the powers of governance to a third party, unaccountable, unelected and irremovable by the electorate, and which is not bound by allegiance should not be a matter for the court?

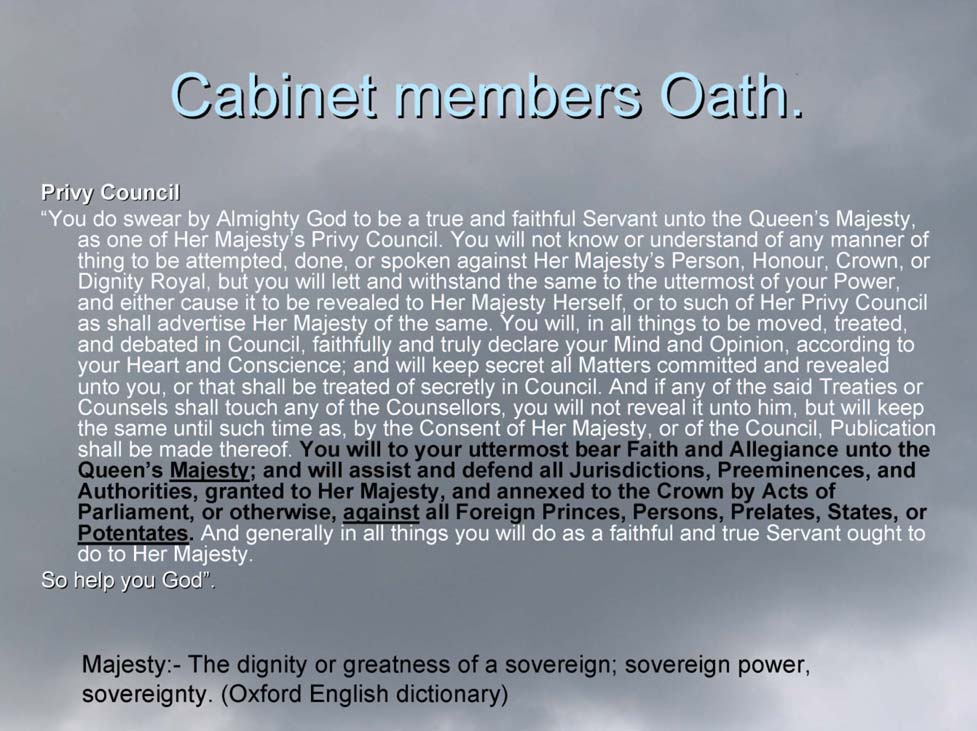

The ‘Majesty’ referred to below is of the office of the Monarch and which is the responsibility of Ministers vigorously to uphold. It is integral to the constitutional birthright of the people.

Lord Chatham on the Constitution

“What if the Commons should pass a vote abolishing this House, abolishing their own House, and surrendering to the Crown all the rights and liberties of the people, would it only be a matter between God and their own consciences, and would nobody else have any thing to do with it? You would have to do with it—I should have to do with it—every man in the kingdom would have to do with it—and every man in the kingdom would have a right to insist upon the repeal of such a treasonable vote, and to bring the authors of it to condign punishment.”

Parliamentary History Lord Chatham 645/6 anno 1770 Re Wilkes

It is plain that the Constitution may never be impliedly repealed by later laws. It is sworn duty to uphold and maintain. Parliament is composed of persons who are bound to observe their duty and the law. They are sworn to true allegiance and by mere common sense, bound to conform to the Constitution. This is simply proven by considering which is superior under theConstitution, the rule of law or the power of Parliament? Clearly there is no purpose in any constitutional law if it is simply abandoned, ignored or overridden directly or impliedly, by increment or wholesale breach. Given that we have laws which have constitutional intent, it must be fact that their authority binds in the intended manner until such time as they are expressly repealed. Contempt of statute is a serious offence as is treason. The law may not be ignored or broken even by Parliament. This was a theme of the recent Metric Martyrs’ case, Thoburn v Sunderland City Council.

The defence hinged on the question of the supremacy of Parliament although it is obfuscated in the judgement which elevates the European Communities Act of 1972 into the status of constitutional law. The defence was based on the theory that Parliament had by continuing the use of the mile and pint by enactment in 1985, expressed its latest will. Under the ‘Leges posteriores priores contrarias abrogant’ rule (earlier law is abrogated by contrary newer law) had impliedly repealed the power vested in the minister under the 1972 Act, to abolish the pound weight in favour of the kilogram. This judgement was important for Laws LJ held that there could be no implied repeal of a constitutional law but only express repeal. The power was deemed constitutional and therefore not subject to implied repeal. Thoburn lost.

This status of our constitutional law is of course obvious to the test of common sense; however our laws have become so convoluted by the assertions of the courts in favour of ‘public policy’ that the wood has become indistinguishable from the undergrowth. Clearly law that is constitutional in content may not be ignored or simply set aside. This is certainly not the status of Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, the Declaration and Bill of Rights, the Coronation Oath and the Act of Settlement which are all current constitutional law.

Second if there in no legitimate way to alter the Constitution indirectly, may it be altered by specific repeal and or new enactment? This is a question of entrenchment and the degree of reinforcement that constitutional law has from being repealed, removed or altered. These questions and comprehension of the details that underly these quandaries will lead to a better appreciation of liberty and the limitations and remedies provided by our Constitution. Forinstance should we consider the rule of law itself to be entrenched? The Coronation Oath and all oaths of office make the rule of law a prerequisite duty of government on attaining office on behalf of the Crown and People. All governments are given direction and purpose by our Constitution which is to defend our liberty, our civil and spiritual rights and properties. That constitutional purpose is of preservation and maintenance not diminution, suspension or destruction.

Suppose a parliament should decide to enact a new law to boil all terrorist to death. Such a law would be in flagrant breach of the Bill of Rights which declares in its text against all cruel and unusual punishments. The Bill of Rights is a statute in force, which for its purpose sets limitation upon governance and provides remedy for oppression. It is directly binding upon the prerogative power of the Crown and it is undoubtedly the duty of all ‘officers and ministers whatsoever’ to obey and uphold it. That juries shall be empanelled is another. Couple this with the no ‘fines and forfeitures before conviction’ (presumption of innocence) and the right to trial from chapter 29 of Magna Carta and it becomes impossible to see how we may be separated from the right to trial by jury and the presumption of innocence by any Parliament! After all these are our absolute rights imposed as limitations on the Crown and prerogative!

Both Blackstone and Dicey thought that the judiciary must be subordinate to Parliament else it would be possible for corrupt or deferential judges to subvert the Constitution as has happened in history. (According to the famous Letters of Junius, Dr Blackstone was at times deferential. See the Letters of Junius August to October1769. in which he successfully embarrassed the Dr (later Sir William) by showing his contradictions using Blackstone’s own commentaries and his famous quote ‘the law is not a matter of opinion’). The real point here is that the independence of the judiciary must be assured so as not to allow them to be brought under any political pressure; but to adjudge only according to the law with justice in mercy, as is their sworn duty. Judgment must not be political but according to law and right. Deference or desire to follow public policy should play no part. The Judiciary’s only true constitutional masters are the law and justice in mercy.

The judiciary have indicated that the redress lies with Parliament. This is contrary to the supremacy of the law. The Constitution recognizes the division of power and the duty of office. The constitution affirms some absolute rights of the subject. The key lies in understanding the true settlement of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the certainty that the supremacy of Parliament is always subservient to the constitutional law in force as common sense and the common law determine. This being so, the proper purpose of government becomes clearly defined by our constitutional law. Due weight should be given to the word maintaine (see below) shown in the preamble of the Coronation Oath Act.

“instead of the arbitrary power of a King, we must submit to the arbitrary power of the House of Commons. If this be true, what benefit do we derive from the exchange? Tyranny my Lords, is detestable in every shape, but none so formidable as where it is assumed and exercised by a number of tyrants. But my Lords this is not the fact, this is not the Constitution, we have a law of parliament. We have a Statute Book and the Bill of Rights.” William Pitt 1st Earl of Chatham 1708 – 1778

The Magna Carta is the first great script in English jurisprudence to create constitutional order and form to limit and to contain the abuse of the governing power. The vital legacy of Magna Carta is the Rule of law itself. The Great Charter was used and abused but its legacy was destined to prevail. It created the rule of law and removed all outlawry. Freedom was to be protected by the law.

It is clear that any genuine constitution must define limitations of power. It is fundamental that a constitutional system will include a means of redress so that abuse will always have a remedy, most importantly where the excesses of governmental power breach the Constitution. Apart from the events of 1215, 1628 and 1688 the inherent right of remedy is recorded in English jurisprudence in the oftenquoted test case of Ashby v White in judgement on the 14th January 1704 Holt CJ : –

“ If the plaintiff has a right, he must of necessity have a means to vindicate and maintain it, and a remedy if he is injured in the exercise or enjoyment of it; and indeed it is a vain thing to imagine a right without a remedy, for want of right and want of remedy are reciprocal.” Ubi jus ibi remedium (where there is a right there is a remedy).

The Magna Carta laid the foundation stone for the supremacy of the law. In its provisions it absolved the subjects of allegiance to the King if he should break its clauses. It went further and recognised that there should be a right for the subjects to use force until redress was given. This is an important principle of redress for no Kingdom which relied upon a system of allegiance could afford to lose the loyalty upon which its authority and power was founded. This principle of redress against unconstitutional governance can be found in Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England 1765 (1st Ed Vol IV. Page 433) “…….have confirmed and exemplified the doctrine of resistance when the executive magistrate endeavours to subvert the constitution; have maintained the superiority of the laws above the king, by pronouncing his dispensing power to be illegal” It was recognised by Locke and Coke but it was ignored by Dicey and his later editor Wade.

Sir William Blackstone considered the authority of the Glorious Revolution and its settlement to be paramount to the liberty of the subject and the undoubted duty of all government. The revolutionary settlement made certain the limitations of the Crown and Government and settled a means for redress if the liberties were in any way infringed. Blackstone again recognised this and cited the revolution as an exceptional precedent in favour of resistance if the abuse should be repeated. So as Junius in his letters to the Public Advertiser did in 1769-70, I too can point to inconsistency in Blackstone. I would not wish to denigrate the Commentaries for they are essential study and a truly great work. It is perhaps out of deference that Blackstone did not completely connect the logic of his analysis. Right and absolute power, are incompatible. He recognised the limitation of the Monarch and the existence of certain duties in the Crown to maintain the subjects’ liberties which he defined as per the Declaration of Rights. There could be no possibility of the law not binding the Crown and Government as the extant quote from the Act of Settlement shows. Our Constitution is law in force.

Bowles v Bank of England 1912 Parker J Chancery Division

“the Bill of Rights still remains unrepealed, no practice or custom, however prolonged, or however acquiesced in on the part of the subject, can be relied on by the Crown as justifying any infringement of its provisions.”

In 1976 in the Court of Appeal Lord Denning M.R., upheld the Bill of Rights with this statement in Congreve v The Home Secretary over a £6 increase in Television Licences.

“These courts have the authority – and, I would add, the duty – to correct a misuse of power by a Minister or his department, no matter how much he may resent it or warn us of the consequences if we do. Padfield v. Minister of Agriculture Fisheries and Food [1968] A.C. 997 is proof of what I say. It shows that when a Minister is given a discretion – and exercises it for reasons which are bad in law – the courts can interfere so as to get him back on the right road. Lord Upjohn put it well when he said at pp. 1061 –1062. ‘A Minister is a public officer charged by Parliament with the discharge of a public discretion affecting Her Majesty’s subjects; if he does not give any reason for his decision it may be, if circumstances warrant it, that a court may be at liberty to come to the conclusion that he had no good reason for reaching that conclusion and order a prerogative writ to issue accordingly.

There is yet another reason for holding that the demands for £6 to be unlawful. They were made contrary to the Bill of Rights. They were an attempt to levy money for the use of the Crown without the authority of Parliament: and that is quite enough to damn them.”

The public trust placed in our politicians or civil servants does not permit them to undermine the Constitution by which they are bound.

Placing Politics Above Law is The Road to Depotism

Where a constitution exists it is paramount that the courts uphold it so that it will always be the pre-eminent active public policy. Conversely when political ambition imposes itself above the law, the rule of law is replaced by dictatorship and despotism Dictatorship, despotism and tyranny are in essence all extreme forms of administrative law. Administrative law seeks to combine the legislative power with the power of enforcement; Sir William Blackstone said “wherever the two powers are united there can be no public Liberty.”

This can be an insidious process. In 1929 Lord Hewart of Bury in his book The New Despotism and as the sitting Lord Chief Justice of England, recognised and clearly warned, of the grave danger posed by the then ready acceptance of administrative law with its tendency to unite the powers of the legislative body with the power of enforcement.

This is the inverse of the rule of law which under English Jurisprudence gives the people the ultimate power of enforcement through the right of jury trial. It is the universal right of the jury to declare a general verdict of ‘not guilty’. Integral to the rule of law is the right of Habeas Corpus, the presumption of innocence and the right to jury trial for any offence that curtails a person’s liberty plus of course parliamentary representation with democratic accountability through election and criminal liability. These common law powers of the constitution should ultimately control all excesses committed by the legislator, even where full statutory authority purports to exist.

It must be realised that our Constitution only places administrative law in the statute book from 1946 with the introduction of the Statutory Instruments Act. Up to this time administrative law was only covered by the Rules Publications Act 1893 and power devolved by acts of Parliament. All such administrative law is subservient and subordinate to our constitutional law e.g. The Coronation Oath, Magna Carta 1215, The Declaration and Bill of Rights 1688/9, The Act of Settlement 1701 & The Treaty of Union 1706.

The front cover of the 1946 Statutory Instruments Act reads:-An Act to repeal the Rules Publication Act 1893 and to make further provision as to the instruments by which statutory powers to make orders, rules, regulations and other subordinate legislation are exercised.

Administrative law is but a branch of the tree when compared with the mighty heart of oak that represents the law and framework of our ancient and indubitable Constitution.

The EU and its proposed new Constitution represent the ultimate in mission creep by the English legislator and its associated establishment. It will subvert the rule of law permanently by placing power of governance in the hands of those who are unelected, irremovable and not accountable to the United Kingdom electorate or tied by allegiance to the Crown and people. The EU is fast establishing a dictatorial power which is self financing and with complete immunity for its officials.

This is contrary to the rule of our law under the existing Constitution of England as are so many other governmental actions, particularly at the current time. The Sovereignty of the nation belongs to the people and is vested in the Crown under our Constitutional terms.

There is and can be no divine right of politicians to diminish our birthright. Politicians represent the will of the people in Parliament only for the constitutionally limited duty with which Parliament is charged.

Constitutional Principles of Power and Remedy

The Constitution is specifically intended, indeed designed to limit the powers of the state with respect to its people. The Constitution sets a standard upon which the performance of governance may be measured and contested and to provide remedy if abused. The whole constitution originates its authority from the common law. Supremacy resides in the law and people, not the Crown or Parliament. It is a matter of constitutional principle and legal fact that, the law is supreme. The rule of law is the antithesis of arbitrary power. Integral to it, is the system of jury trial. It places the power of law enforcement in the hands of the people. This is a most vital safeguard against despotism. The English Constitution’s function is to protect the rights and liberties of Englishmen. These are the ‘birthright of the people’

The fundamental rights and liberties are listed in the preamble of the Coronation Oath Act 1688 which declares that the oath is taken for the purpose of “Maintaining our spiritual and civil rights and properties”. It is a contract with the people which makes it the permanent duty of the Crown, and the Crown in both Government and Parliament. This contracts the Monarch to govern only according to the statute, common law and the custom and to ‘cause law and justice with mercy to be used in all judgements’. All power of governance is vested in the Crown. The two Houses of Parliament may upon their concurrence offer bills for Royal Assent. A bill is not enacted until it has been authorised by the Sovereign power.

Whilst the enacting power (a royal prerogative) of Royal Assent is entirely vested with the monarch it is contracted only to be used in accordance with the constitutional law. This is a limitation and essential safeguard to protect the people from any over mighty governance. It was used to defeat the Divine Right of Kings; a claim of absolute power by the Stuart monarchs. The oath ascertains the supremacy of the law, not the supremacy of the Crown or of Parliament. There is certainly no Divine Right of Politicians.

The Coronation contract is of the crown owing allegiance to the Constitution. The people give allegiance to the Crown. Here is a system of mutual protection for there is a constitutional interdependence. The Magna Carta made provision for the people to use any means including force if the Crown is found to be in its breach. This right of resistance is the ultimate remedy. The use of petition has historically become the means to seek constitutional remedy. This right of petition is secured for the people by our constitution.

The Coronation contract also protects the people from abuse of power by formalising and causing the separation of power. It separates the authorisation (Royal Assent) from those who determine its content or application (in Bills); the Lords and Commons in Parliament. This separation prohibits the formation of absolute power from falling into despotic or tyrannical misuse and the jury inhibits draconian enforcements. The Monarch, the Lords or Commons may not arbitrarily suspend or dispense with the law. The law may be made or adjusted only by enactment by the tripartite body of Parliament.

The Monarch is the people’s repository of all the sovereign powers of the state.

The limited range of remaining prerogatives may not be used in repugnance of the law.

The monarch is bound by law. The Monarch may only exercise powers in accordance with the constitution and law in force. Thus the rule of constitutional law is a rule and process of governance for Parliament to observe. It is for the protection of the people. The maxims ‘no parliament may bind its successor’ and ‘the sovereignty of the Crown inParliament’ have become confused through partial misunderstanding to the detriment of our Constitution. No combination of these maxims can or may absolve the crown, its ministers or Parliament, from owing allegiance, or being at all times in compliance with constitutional law. There can be no implied repeal of constitutional statutes. Such anomalies as implied repeal weaken the rule of law, confusing interpretation, and may tend to the breach of the Coronation Oath and constitution. Constitutional repeal must be by express enactment and only where the parts of the constitution are not protected by the entrenchment of Oath. The most fundamental and important is the entrenchment of the whole process of the rule of law. It is contracted permanently by the Coronation Oath being the fundamental by which governing power is held.

That which constitutionally binds the Monarch is a restriction upon Her Majesty,

Her Government and all Parliamentary power. The Monarch may do no wrong but should refuse by her negative power (the right to withhold assent) to let wrong be done. Sir William Blackstone confirms this. Whilst the monarch accepts the advice of ministers, they must only advise to do that which complies with the constitution. Plainly no monarch is free to assent to advice that conflicts with the constitution in force.

There is no authority in Parliament to pass any power of governance in England to those who hold or owe no allegiance. There is no constitutional authority for Parliament deliberately to breach the constitutional laws by new conflicting enactment. There is a natural duty resulting from the logic of our constitutional law to debate and resolve conflicts, if necessary by prior repeal. We must put an end to this form of ‘legal’ abuse, particularly though the misapplication of party politics.

Most but not all of our constitution is written:- the Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, the Declaration of Rights, the Bill of Rights, the Act of Settlement and the Acts of Union etc. It has evolved over centuries with the expenditure of much blood. It has been abused and corrected many times. It was finally settled by the Glorious Revolution 1688/9.

The Judicial function is to be the independent arbiter between party and party or party and government under the terms of our constitutional law. The courts are bound to declare upon the constitutionality of an Act where it may prove to be an action of unconstitutional governance. The great examples of the Magna Carta, the Petition 1628, the Declaration & the Bill of Rights 1688/9 make this duty of the court utterly plain.

Judgement may only be given in accordance with the constraints of the constitutional laws in force. At all times the presumption of law and justice in mercy must be upheld and used in all judgements. This is the trust and the pre-eminent publicpolicy reposed in the judiciary.

The right of petition to the Monarch is an appeal direct to the source of power, the Monarch is under oath and at law, bound to provide remedy. Where there are rights there are remedies. Politicians and Parliament must abide by the terms of reference and duty to the Constitution.

A fixed or certain standard with protection and remedy are the true purpose of our Constitution. We must reclaim our Constitution and the rule of our law from the supposed divine right of our politicians.