Licensing Despotism

Constitutionality of QUANGOs ULEZ

(Quasi non Governmental Organisations)

Consideration involving some Constitutional Principles and the potential consequences of their violation

- The presumed ‘Sovereignty of the Crown in Parliament’ is not an unlimited Power to legislate but defines a Constitutionally limited body for our Governance bound by lawful duty to uphold the ‘Liberties of the Subjects’

- Imposing perjury upon the Crown. Imposing unconstitutional governance and engaging breach of the constitutional restraints intended to limited the powers of Parliament

- Administrative lawlessness

- The separation of the People from their Courts

- Ministerial abuse of the Royal Prerogative

- The irrelevance of the Doctrine ‘No Parliament may bind its successors.’

- The independence of the Judiciary

- Judicial duty

- Proof of the grant of Constitutional authority for the courts to declare the unconstitutional implementation of rules regulations and enactment invalid, as being ‘no law at all’

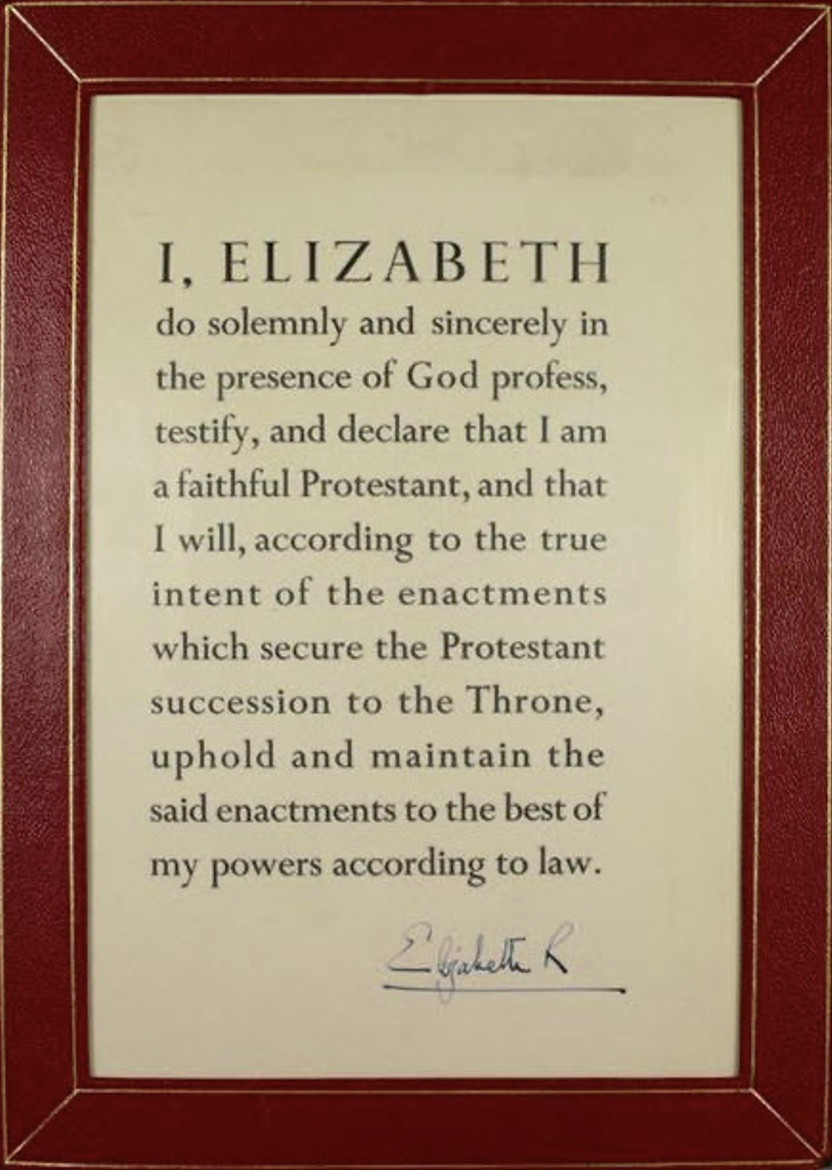

Accession Declaration Oath

& in Establishment of the Declaration and Bill of Rights 1688/9

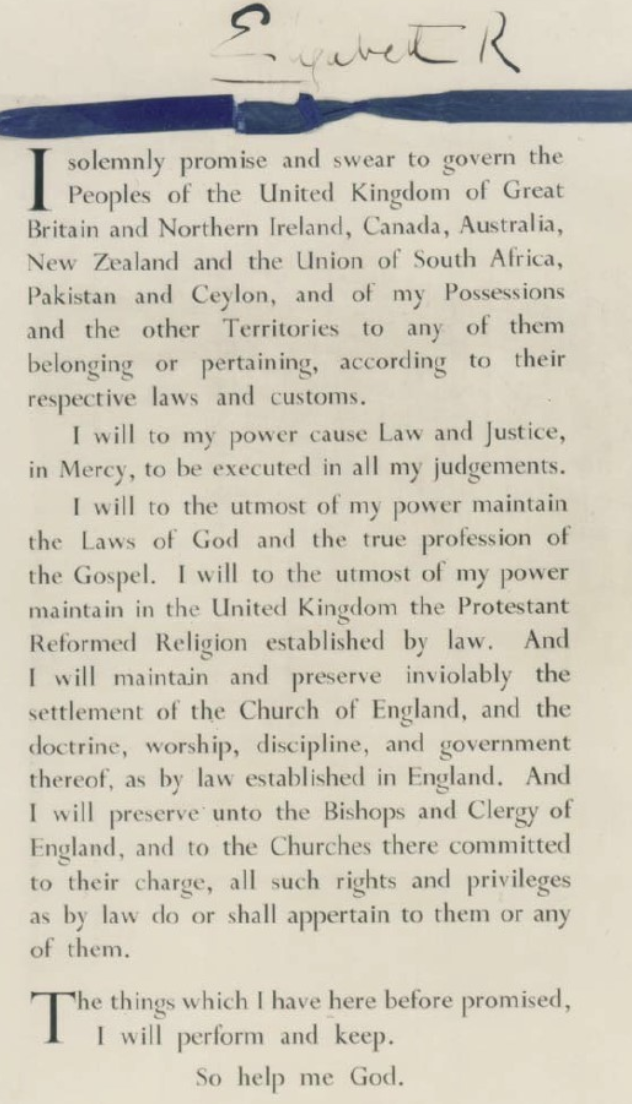

Coronation Oath.

It is my contention that all arbitrary power is denied in our governance. It ought not to be doubted that this was the intention of the Settlement. It is recorded in the Declaration and Bill of Rights:-

The Bill of Rights requires the Crown to ensure that its clauses are observed as widely as possible. It Specifically calls upon the judiciary to interpret it in the widest possible way for the benefit of the Subject’s liberty.

Crucial texts:-

“…their undoubted rights and liberties, and that no declarations, judgements, doings or proceedings to the prejudice of the People in any of the said premises ought in any wise to be drawn hereafter into consequence or example;…”

“That levying money for or to the use of the Crown by pretence of prerogative, without grant of Parliament, for longer time, or in other manner than the same is or shall be granted, is illegal;”

Attorney-General v Wiltshire United Dairies 1921 Court of Appeal

Lord Justice Atkin: ‘Though the attention of our ancestors was directed especially to abuses of the prerogative, there can be no doubt that this statute declares the law that no money shall be levied for or to the use of the Crown except by grant of Parliament. We know how strictly Parliament has maintained this right – and, in particular, how jealously the House of Commons has asserted its predominance in the power of raising money.

In these circumstances, if an officer of the executive seeks to justify a charge upon the subject made for the use of the Crown (which includes all the purposes of the public revenue), he must show, in clear terms, that Parliament has authorized the particular charge.’ and ‘It makes no difference that the obligation to pay the money is expressed in the form of an agreement. It was illegal for the Food Controller to require such an agreement as a condition of any licence. It was illegal for him to enter into such an agreement. The agreement itself is not enforceable against the other contracting party; and if he had paid under it he could, having paid under protest, recover back the sums paid, as money had and received to his use.’

Attorney-General v Wilts United Dairies Ltd: HL 1922

Held: The appeal failed. The levy was unlawful. Lord Buckmaster said: ‘Neither of those two enactments enabled the Food Controller to levy any sum of money on any of his Majesty’s Subjects. Drastic powers were given to him in regard to the regulation and control of the food supply, but they did not include the power to levy money, which he must receive as part of the national fund. However the character of the transaction might be defined, in the end it remained that People were called upon to pay money to the Controller for the exercise of certain privileges. That imposition could only be properly described as a tax, which could not be levied except by direct statutory means.’

Gosling v Veley was cited: 1850Wilde CJ said: ‘The rule of law that no pecuniary burden can be imposed upon the subjects of this country, by whatever name it may be called, whether tax, due, rate, or toll, except under clear and distinct legal authority, established by those who seek to impose the burden, has been so often the subject of legal decision that it may be deemed a legal axiom, and requires no authority to be cited in support of it.’

It would seem to pass an arbitrary power to the various authorities to raise funds as they see fit for any vehicle using the roads. It appears to pass powers of conviction by the imposing of financial charges and penalties which are potentially extracted without any conviction in a court r path to a common law test by the people. Is a discounted ‘charge’ payment for instance, a payment without a conviction? Is it in principle a form of extortion? Is it designed to evade the court passing a power of induced self condemnation to the administration and in conflict with the separation of powers?

The implementation of penalty charge notices with discounts if you pay promptly without any court hearing or the imposition of a tribunal to hear cases which is not a customary court of law. Where juries are empanelled the power of conviction is in the hands of one’s peers / the People not the State (Note a command of Magna Carta). This is an important separation of power between the people and the State. All law placed in front of a Jury becomes subject to the Common law test of the circumstances surrounding the case and each Jury has a right to declare a not guilt verdict if it deems the non enforcement of that law in that case, appropriate. Whereas a tribunal appointed by the Minister appears to violate the Constitutional Separation of Powers, does the common law test exist is there an appeal path to it? All these features would seem to intrude upon the Bill of Rights clause about levying of monies by arbitrary power, and also other clauses about excessive fines, jury trials and ‘pernicious Courts’ and the maintaining of a fully independent judiciary:-

“That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted;

That jurors ought to be duly impanelled and returned, and jurors which pass upon men in trials for high treason ought to be freeholders;

All grants and promises of fines and forfeitures of particular persons before conviction are illegal and void.”

There are those who might argue that the doctrine ‘No Parliament may bind its successors’ invalidates this. They are very wide of the mark for the Doctrine can have no bearing upon the law in force, for it is a doctrine about the power to repeal law not to a doctrine to override or by-pass Statutes in force or place them in anyway aside or to excuse the breaching of solemn Oaths. To legitimately set the Declaration and Bill of Rights aside and the renunciation of the binding principles of the oaths for duty of office without very formal and express rearrangements has to be illegitimate. The Monarchy would in all likely hood have to abdicate at very least if such an undertaking was required.

“The Bill of Rights still remains unrepealed, no practice or custom, however prolonged, or however acquiesced in on the part of the subject, can be relied on by the Crown as justifying any infringement of its provisions.”

“By renewing the licence before the existing licence expired the increased fee has been avoided and we have been instructed by the Home Office, for whom we act as agent in operating the television licensing system, not to allow this. I am, therefore, required to ask you to remit the additional fee of £6 together with the enclosed receipt form within 14 days … In the event of failure to pay the additional fee, we have been instructed by the Home Office to revoke the licence taken out in advance. It will then no longer be valid and you will have to renew your licence which expired at the end of March 1975 at the new rate”.

A lot of timid ones succumbed to that threat. They paid up the £6. But the strong minded ones did not. They went on using their television sets under their £12 licences. Two months later, as a sop, the Home Office modified their threat. They said to the recalcitrants: ‘Pay up the £6 or we will revoke your new licences after eight months. By that means we will make you pay at the increased rate.’ I will again set out their very words of the letter of 27th August 1975:

After getting that letter, again the ranks of the overlappers broke. Some paid up. But others stood firm. Their £12 licences were still in force. They went on using their television sets. On 11th November 1975 the Home Office gave another warning:

“If you would now send me a remittance for £6…I will arrange for the validity of your licence to be extended to 31st March I976. I am sorry to have to remind you that, unless you do so, your television licence will be revoked as from 1 December 1975. If thereafter you use a television set without holding a valid current licence, I am afraid that you will render yourself liable to prosecution….”.

A few days later the Home Office carried out their threat. On Wednesday 26th November 1975 – even whilst an appeal to this court was known to be pending – they sent out notices revoking the £12 licences with effect from 1st December 1975. I set out the words of the letter of revocation:

“This sum of £6 has not been received. Accordingly, I am directed by the Secretary of State to give you NOTICE that the LICENCE obtained by you in March 1975 is hereby REVOKED with effect from 1 December 1975….If you are to continue using a colour television set, you should take out a fresh licence promptly at the current fee of £18”.

If those notices are valid, every one of the overlappers must stop using his television set or be guilty of a criminal offence. They appeal to this court to help them.

Mr Congreve is their leader. His case is brought to test all of them. Counsel on his behalf submitted that the demand of the Home Office for £6 was an unlawful demand; that the licence was revoked as a means of enforcing that unlawful demand; and that, therefore, the revocation was unlawful.

Counsel for the Minister submitted that, by taking out an overlapping licence, Mr Congreve was thwarting the intention of Parliament; that the Minister was justified in using his powers so as to prevent Mr Congreve from doing it.

Now for the statutory provisions. The granting of television licences is governed by the Wireless Telegraphy Act 1949, and the regulations made under it. The 1949 Act said (so far as material):

1.-(1) No person shall … install or use any apparatus for wireless telegraphy except under the authority of a licence in that behalf granted by the [Minister].

Now for the carrying out of the statutory provisions. Undoubtedly those statutory provisions give the Minister a discretion as to the issue and revocation of licences. But it is a discretion which must be exercised in accordance with the law, taking all relevant considerations into account, omitting irrelevant ones, and not being influenced by any ulterior motives. One thing which the Minister must bear in mind is that the owner of a television set has a right of property in it; and, as incident to it, has a right to use it for viewing pictures in his own home, save insofar as that right is prohibited or limited by law. Her Majesty’s subjects are not to be delayed or hindered in the exercise of that right except under the authority of Parliament. The statute has conferred a licensing power on the Minister; but it is a very special kind of power. It invades a man in the privacy of his home, and it does so solely for financial reasons so as to enable the Minister to collect money for the Revenue. It is a ministerial power which is exercised automatically by clerks in the Post Office. They cannot be expected to exercise a discretion. They must go by the rules. The simple rule – as known to the public – is that, if a man fills in the form honestly and correctly and pays his money, he is to be issued with a licence.

Now for a first licence. Test it by taking a first licence. Suppose a man buys on 26th March 1975 a television set for the first time for use in his own home. He goes to the Post Office and asks for a licence and tenders the £12 fee. He would be entitled to have the licence issued to him at once; and it would be a licence to run from the 26th March 1975 until 29th February I976. I say ‘entitled’, and I mean it. The Home Secretary could not possibly refuse him. Nor could he deliberately delay the issue for a few days – until after 1st April 1975 – so as to get a fee of £18 instead of £12. That would not be a legitimate ground on which he could exercise his discretion to refuse. The Minister recognises this. He allows newcomers who apply for a licence before 1st April 1975 to get their licence for the next 12 months for the £12 fee.

“[the Minister] is a public officer charged … with the discharge of a public discretion affecting Her Majesty’s subjects; if he does not give any reason for his decision it may be, if circumstances warrant it, that a court may be at liberty to come to the conclusion that he had no good reason for reaching that conclusion and order a prerogative writ to issue accordingly”.

Are those good reasons? I cannot accept those reasons for one moment. The Minister relies on the intention of Parliament. But it was not the policy of Parliament that he was seeking to enforce. It was his own policy. And he did it in a way which was unfair and unjust. The story is told in the report of the Parliamentary Commissioner. Ever since 1st February 1975 the newspapers had given prominence to the bright idea. They had suggested to readers that money could be saved by taking out a new colour licence in March 1975 instead of waiting till after the 1st April 1975.

My conclusion is that the demands made by the Minister were unlawful. So were the attempted revocations. The licences which were issued lawfully before the 1st April 1975 for £12 cannot be revoked except for good cause; and no good cause has been shown to exist. They are, therefore, still in force and the licensees can rely on them until they expire at the date stated on them.

“By levying money for and to the use of the Crown by pretence of prerogative for other time and in other manner than the same was granted by Parliament;”

The Remedy:-

“That levying money for or to the use of the Crown by pretence of prerogative, without grant of Parliament, for longer time, or in other manner than the same is or shall be granted, is illegal;”

Royal Assent is granted to Bills which enacts them into Acts of Parliament. The Bills are transformed into enactment by the Crown’s grant of ‘Royal Assent’ because it is the Crown who actually holds the Power of Governance under the customary constitutional and mandatory arrangements for Sovereignty of our Constitution and the Rule of Law. The individual Houses are component parts but do not constitute Parliament.

Returning to the differences between what has been upheld by the courts and what is stated additionally in the clause for the ‘levying’ of money it becomes clear we need to consider the extra words:-

Being that this is a direction in our current constitutional law commanding the Crown and all who serve it, it must surely amount to a constitutional obligation for all in governance and all in Parliament to obey. The Crown may not be advised by its Ministers to breach this. Are we not by tolerating ULEZ entering the dangerous road warned about in the two Judgements aforementioned?

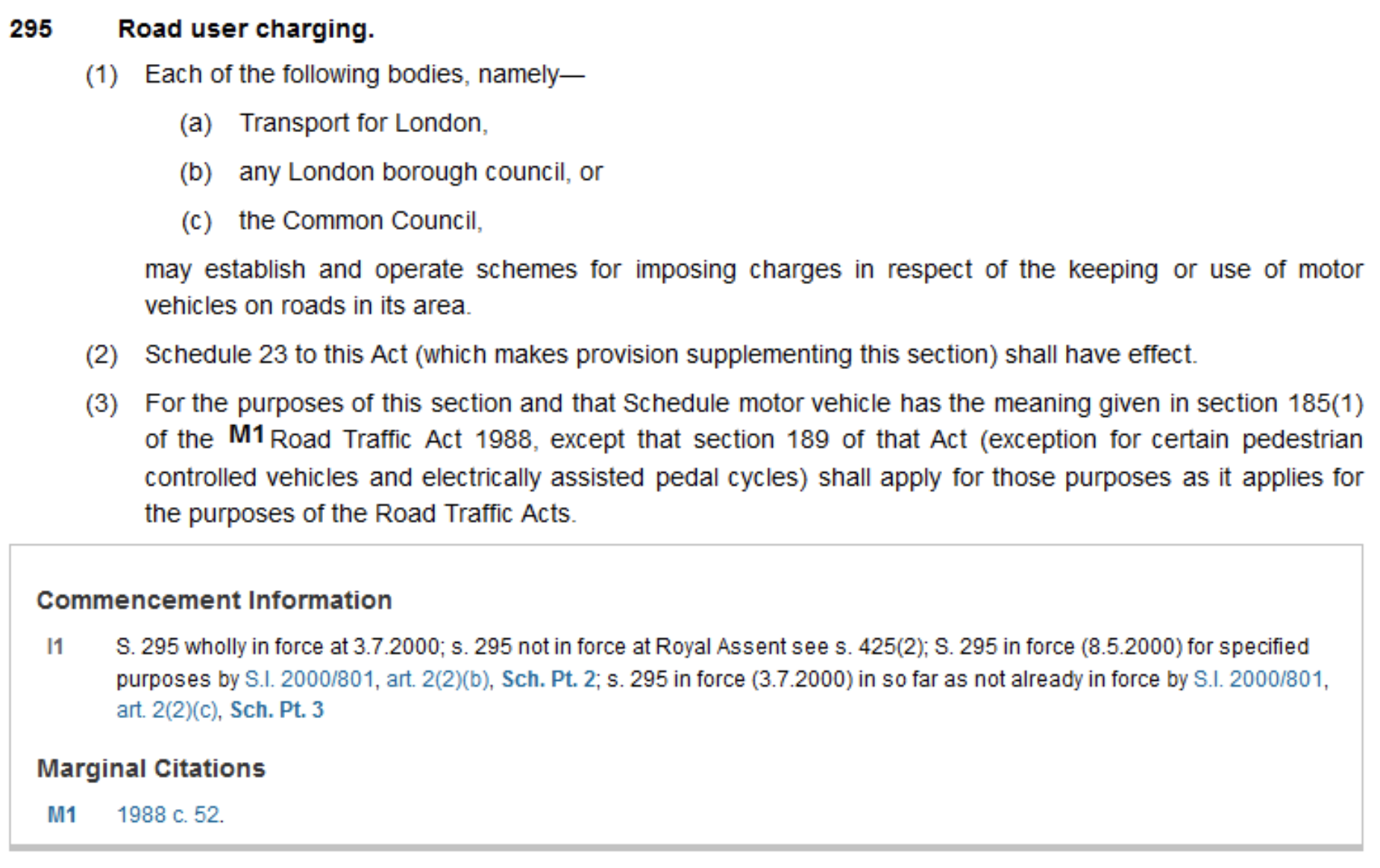

Analysing the ULEZ affairs, we can see that the root enactment creating the Greater London Authority Ch29 1999 at clause 295 does not go beyond stating that the bodies mentioned may create systems for traffic regulation and support that with making charges. The various part are then enabled by the introduction of Statutory Instruments which are effectively the direct prerogative orders of the Crown and subordinate in nature to Enactments.

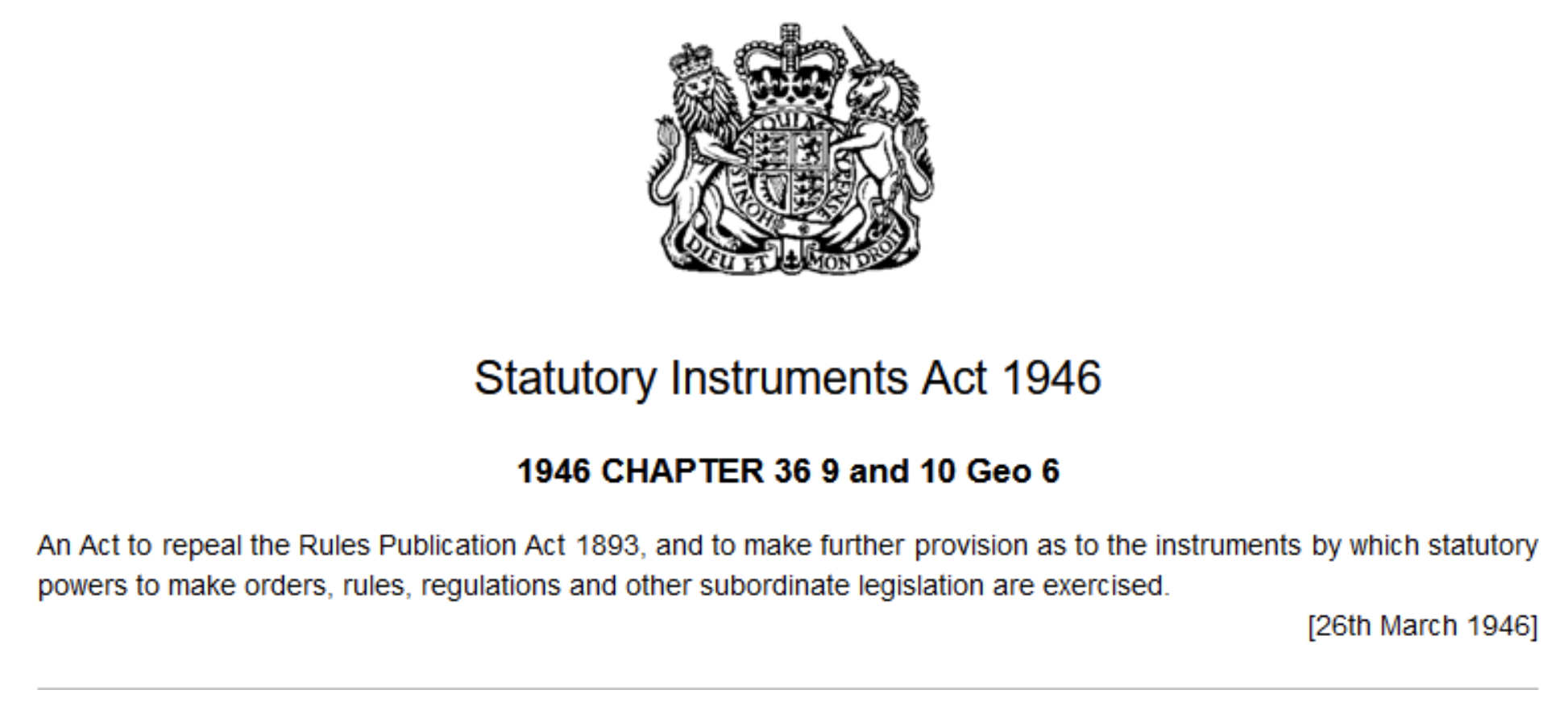

The Subordinate nature of Statutory Instruments is declared in the founding enactment here is the title part of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946

It is readily seen that the devolving of charge making regulations and powers has ostensibly been delegated to introduction by Statutory Instrument for constructing the regulations for levying of money and more. This I perceive then places a degree of arbitrary power to levy money in the hands of the Executive to set up virtually unlimited schemes under the broad remit of Schedule 295. The Statutory Instruments then become the source of the defined regulation along with the Ministerial orders thus the particular rules made for the levying of money do not have specific Grant of the current Parliament. Is this modus operandi is equivalent to a Licensed Despotism? It would seem to exhibit arbitrary power to define the actual charges, the levying et al. Does it place the Crown in violation of its constitutional obligation and undertaking? And if thus then, the ‘no taxation without representation’ prohibition in essence seems violated all in favour of a quasi subordinate from of governance.

Violate ULEZ and its pay up within 14 days and pay £90 now or else pay £180. You may appeal to the Tribunal. If you pay you won’t have to go to court, and we offer you a discount! Whoops its not a court of law it is a Tribunal set up under the regulations of the Minister.

By issuing and causing to be executed a commission under the great seal for erecting a court called the Court of Commissioners for Ecclesiastical Causes;

The Remedy

That the commission for erecting the late Court of Commissioners for Ecclesiastical Causes, and all other commissions and courts of like nature, are illegal and pernicious;

And several grants and promises made of fines and forfeitures before any conviction or judgement against the persons upon whom the same were to be levied;

The Remedy

That all grants and promises of fines and forfeitures of particular persons before conviction are illegal and void;

Is a Penalty Charge notice requiring payment in direct violation of this clause against levying money before conviction? Is there a common law test of breach of the regulation or is it an absolute offence. If the latter, does it not intrude upon the Separation of Power of enforcement only by the People and place direct enforcement in the hands of the State?

And whereas of late years partial corrupt and unqualified persons have been returned and served on juries in trials, and particularly divers jurors in trials for high treason which were not freeholders;

That jurors ought to be duly impanelled and returned, and jurors which pass upon men in trials for high treason ought to be freeholders;

And excessive bail hath been required of persons committed in criminal cases to elude the benefit of the laws made for the liberty of the subjects;

And excessive fines have been imposed;

And illegal and cruel punishments inflicted;

That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual

punishments inflicted;

Does all this not add up to declarations, judgements, doings or proceedings to the prejudice of the People being taken into consequence and example against the principles of the Bill of Rights?

“…their undoubted rights and liberties, and that no declarations, judgements, doings or proceedings to the prejudice of the people in any of the said premises ought in any wise to be drawn hereafter into consequence or example;…”

That it is the right of the subjects to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal;

A general power of devolvement as listed in the Greater London Authority Act 1999 at 295 seems to separate and diminish the People’s representation through Parliamentary scrutiny. It allows for a degree of arbitrary rule and regulation to take hold by the whims of administrative arrangement and becoming autocratic in nature.

Lord Hewart of Bury warned that such ‘delegations’ or Licensed Despotism as he titled his book separated the People from their courts and most particularly from their representative governance in the House of Commons. Placing autocratic powers directly to the Executive and its administration for years to come or until repealed for the levying of monies. How may this or any newly implemented financial levying qualify as a ‘particular’ charge authorised by a specified ‘Grant of Parliament‘?

“how strictly Parliament has maintained this right – and, in particular, how jealously the House of Commons has asserted its predominance in the power of raising money.”

Conviction is by ones peers which is not intended to become a general power of the State and its administration. It is my view that these ancient bulwarks of our Constitutional protection might and should be tested in the Courts and by Petition of Right.